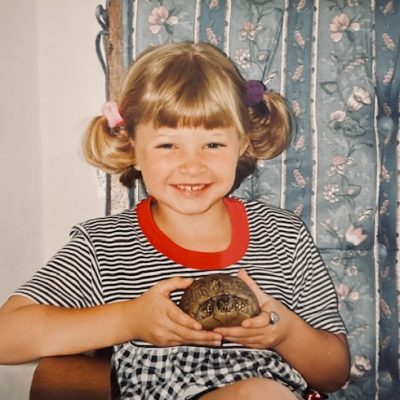

When I was growing up, I had a box turtle named Todd, who used to roam freely around our house while I pretended that he loved me as much as I did him. One day, Todd and I played together in the front yard. He sat seemingly lifeless beside me, tucked away in the comfort of his shell as I played in my world of make-believe. I always respected Todd’s ability to shut himself out from the outer world whenever it became too much, and I often wished I could do the same.

At some point, I forgot all about Todd as I aimlessly rode my bike around the block while he sat alone, unbothered. Hours passed, and as night fell, I remembered him. I rushed outside into the darkness, but he was gone.

As I mourned the loss of my best reptilian friend, I didn’t know that he was alive and well. On any other day, Todd would have given in to his primitive instinct to remain safely in his shell, but on that particular day, he gave in to a different impulse- to live.

Todd must have extended his scaley turtle limbs out wide and steadily put forth the effort to travel to an unknown land. Who knows how far Todd would have gotten on his journey if my dad had not spotted him two days later, an entire two neighborhood houses down from ours.

My dad carried him back to captivity, where we were reunited. As I looked into his half-open shell, I saw a new spark of life glimmering in his small, slanted eyes. He came back a changed turtle. And how could he have remained the same after defying domesticated box turtle odds and breaking free, past his resistance into the unknown? Todd returned, knowing what it was like to wake up with the sunrise and how to sustain himself with neighborhood dandelions while basking undisturbed in the desert sun. He exchanged the safety of his shell, for a more immersive experience with the outer world.

He must have felt alive.

I often think of Todd when I notice my primitive impulse to turtle inside and close myself off from the outside world when I no longer wish to be bothered. Inside my shell, I live in my wild imagination and create a peaceful world where all is easy- including motherhood.

In this world, my toddler no longer yells at elderly women who mistakenly say ‘hello‘ to him. Instead, he graciously exchanges pleasantries, and we continue about our day tantrum-free and lighthearted. Here, elevator doors open with welcoming arms, and my son greets the new mother holding her infant with a smile instead of saying, ‘I don’t like that baby’ for all to hear. No longer must I wrestle him to the ground to dress him, or answer another ‘why’ question, because he already holds the answers.

Oh, this would be the life.

Or so I think. Until I remember that Todd felt most alive when he chose to live outside his shell.

Even so, I continue to convince myself I could live in this disillusioned world forever- except I can’t because my son appears and climbs into my lap with the book Pancakes, Pancakes! by Eric Carle and requests that I read to him. The story begins with a boy who asks his mother for a giant pancake. His mother agrees, but only if he helps to make it. The boy travels to the field with a donkey to harvest wheat, takes it to the mill, and works with the miller to turn it into flour. Then, he gathers eggs, milks the cow, churns butter, and finally, after much effort, the boy and his mother make a giant pancake in a frying pan over a burning fire.

The boy eats the pancake with a new spark of life glimmering in his wide-open eyes. He returned to that kitchen a changed boy. And how could he have remained the same after staying committed to such a task despite experiencing moments of challenge and hard work? He overcame domesticated teenage odds and set out on an adventure when many would have given up on the pancake after realizing it would require them to get dressed and go outside.

The boy must have acquired skills and knowledge from working alongside the land, community members, and his mother to accomplish a task. All his efforts likely added to his character with qualities like patience, fortitude, and courage to help him overcome future challenges. This boy’s heart must have felt full after connecting with natural sources that helped to sustain him. I bet gratitude swelled inside him when lying his head to rest that night after walking, chopping, milking, and churning, all before noon.

The boy exerted effort to live outside his shell and engage with the world around him rather than escape inside.

He must have felt alive.

Carle’s story reminded me of making pancakes with my Grandma Gladis. Gladis was born on a farm in Wilber, Nebraska, in 1922, when radios broadcasted the local news and modern refrigerators were a luxury. The world accelerated at such a rapid pace throughout my grandmother’s lifetime. She watched as people soared the expanse of the sky with the invention of the jet engine. She saw the rise of microwavable meals quickly devoured after minutes of waiting. She witnessed the advancement of the first computer, which eventually evolved into a high-speed machine with endless access to ‘everything,’ while landline phones were replaced with personal cellular devices that many stopped answering.

The hurriedness of the modern world did not take my grandmother with it. As the world sped up, Gladis held on to the slower pace of doing things. She took her time to understand life rather than rush to judgment. She paused to note life’s beauties and stopped to learn the names and stories of all she encountered. Her world was slow, deliberate, and deeply connected to the rhythms of life. Gladid did not need to hurry, even through moments of discomfort, because there was nowhere she was trying to go other than immersed in whatever was in front of her.

Many would agree that Gladis’ piercing blue eyes glimmered with life. Her presence and attention to simple delights pulled others into her light and changed them. And how could one have remained the same after experiencing Gladis’ slower way of doing things? She made each person feel seen and loved with each meal she prepared and every conversation she engaged in. She did not attempt to busy herself with endless issues from across the globe. Instead, she left her front door open for her neighbors that needed a listening ear. There were many who walked through that door.

Gladis overcame modern-day odds and remained unplugged from the anxieties and unattainable picture-perfect internet lives. She spent her energy learning to remain steadily connected to tasks of daily living instead of falling for the lie that she could obtain fulfillment quickly and easily. Overtime, her participation with life filled her heart with enough love to share with a world in need. There were many who received this love.

I used to think Gladis moved at a turtle’s pace. Now, I believe she moved at a pace our world has forgotten. She attentively lived outside of her shell, and because of that, she lived a full and rewarding life that helped to steady the lives of those she touched.

And she never once bought a box of microwaveable pancakes.

Moments after setting down Carle’s story, I hear my son screaming for my attention in the next room. I could feel the pull to retreat—to lose myself in an imagined world where motherhood was easy and perfect. But then, I remembered Todd, Carle’s story, and my grandma.

Rather than hurry to plug into my non-dualistic reality or rush to a place in my mind that doesn’t exist, I commit to remaining outside of my shell. Here, I extend my limbs to all of life and embrace what lies ahead. I use my efforts to stay in my messy, unpredictable, wonderful reality.

My efforts change how I feel, and I experience a surge of joy that fills my glimmering eyes with life and connects me to all who have lived well before me.

And in this single moment, I feel alive.