The practice of yoga has developed and molded into new ways to fit society’s needs and cultural values. Historically, yoga has been adjusted by different groups, thinkers, authors, and practitioners. The meaning and practice of yoga will change from place to place based on different cultures’ interpretations of yoga. The purpose of yoga is also highly dependent on the practitioner’s own beliefs and experiences surrounding it. There is great malleability in the word yoga itself. The extensive semantic range embedded in the term has allowed yoga to change and adapt over time.

It is important to understand yoga’s history because this knowledge may influence your current practice, definition, and beliefs surrounding yoga. In part one of Yoga’s History, we explored the origin of the tradition, popular ancient texts, and early philosophical ideals of yoga (click here to read this post). In part two of The History of Yoga, we will look at the development of postural yoga, how this practice made its way to the West, and how yoga evolved into what it is today.

Medieval Period

The Tantras

Tantra’s teachings arose as a type of spiritual movement in response to the Vedic texts and traditions. The Vedas were a symbol of spiritual, sacred, and unchallengeable knowledge; however, this divine knowledge was not accessible to everyone. Unlike the Vedas, Tantra does not require renunciation. Meaning those with family obligations, work to do in the world, and desires to be fulfilled can also be on the path of learning to live and grow beyond one’s limitations.

What Tantra Is Not

Tantra Yoga continues to be misinterpreted by many because pieces of the tradition were extracted and turned into something to gain widespread interest. In the ’70s and ’80s, Western teachers began offering “spiritual” sexual practices called Tantra. The evidence of sexual practices are very few within the Tantras and represent a small sliver of the pie. Those examples were only available to very advanced practitioners and performed in very complex and elaborate ritual systems. Unfortunately, the false beliefs surrounding this tradition have confused the purpose of Tantra’s practices and philosophy.

What Tantra Is:

Tantra is the name for a type of scripture or text. Tantra in Sanskrit means “to weave.” There are hundreds of Tantras written around the 6th century that represents a vast range of traditions. The idea is to weave aspects of spirituality into daily life rather than keep these two things separate. The practice embraces the idea that all of life is sacred, not just those moments on your Yoga mat. The purpose of Tantric practices is to help an individual realize the beauty and sacredness of life, thus making the world a better place to live in. Tantrics placed a much greater emphasis on practice than on philosophical hypotheses. They also welcomed meaningful theories and methods from both Vedic and non-Vedic sources.

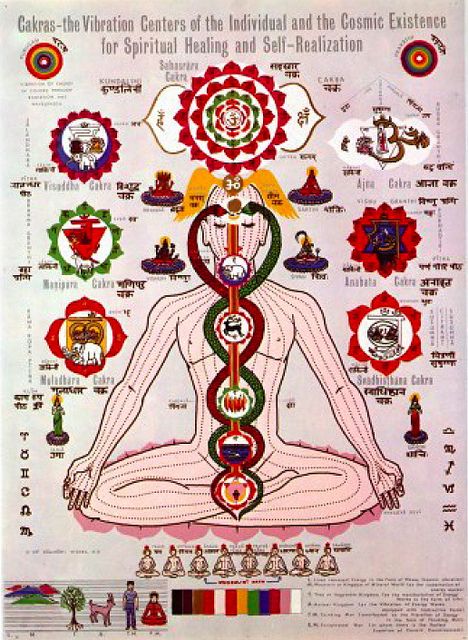

Tantra techniques are a science aimed to expand, channel, and protect energy to liberate an individual. There are numerous teachings on yoga in these texts. Practices found in the Tantras that are a part of the Yoga tradition include:

- Chakras (energy centers)

- Nadis (energy channels)

- Prana (life force energy)

- Meditation

- Visualization practices

- Kundalini (energy)

Hatha Yoga

In the 12th century and onwards, new Sanskrit texts emerged that promoted Hatha Yoga’s ideas and practices. Hatha Yoga built on earlier yogic ideals and also integrated new methods from the Tantras. Many religious and philosophical traditions adopted and utilized the techniques of Hatha Yoga. These practitioners later wrote scriptures or texts about their experience.

The Hatha Yoga Pradipika is one of these texts. Much of our understanding of Hatha Yoga came from this book. It has become the most influential and well-known text on Hatha Yoga. About 50% of the verses are cut and pasted from earlier yoga texts. It’s a compilation and synthesis of previous traditions and claims Hatha Yoga is the primary vehicle to obtain liberation.

There was a shift during the emergence of the Tantras and Hatha Yoga texts. The teachings we now refer to as a part of the yoga tradition were once strictly renunciate traditions. Hatha Yoga became popularized because these practices were accessible to everyone, regardless of religious or philosophical background. The authors did not impose religious systems onto the texts but instead emphasized the techniques and methods. Ordinary householders could access these teachings without renouncing the world or abstaining from life’s pleasures. References to female practitioners also were made during this time.

Another shift during this time, was the emergence of several yoga postures, known as asana. Postures are one of the key practices of Hatha Yoga. The earliest textual sources of the term asana described a seated posture for meditation, breath control, or visualization practices. This is not to suggest there were no non-seated postures in the ancient and classical world. They just weren’t described as asanas, but instead, as tapas (self-discipline or heat). Over time non-seated postures are described in the Hatha Yoga literature. The shift from seated to non-seated asanas may have arisen due to the new emphasis on the body and bodily techniques during the Tantras and Hatha period. Asanas were now being used more dynamically to move energy rather than serving as firm seats for mediation. According to the Hatha Yoga Pradipika, “One should perform asana, for it results in steadiness, freedom from disease, and lightness of body.”

The methods of Hath Yoga are mind-body techniques. It is a system that sees the link between the mind, body, and breath. These methods include:

- Asana= Physical postures both standing and seated for meditation and pranayama.

- Satkarma= six actions for cleansing, purifying, and strengthening the body

- Pranayama= breath extension and control

- Kumbhaka= breath retention or holding

- Mudra= bodily seals

- Bandha= bodily locks

- Dharana= fixation (inner object like chakras)

- Dhyana= meditation/visualizatio

- Samadhi= Liberation

Modern Yoga

Transcendentalists Dabble In Yoga

In the early 1800s, prominent intellectuals, philosophers, and artisans collectively became known as the Transcendentalists. Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau were a part of this movement. They gained access to early English translations of Indian scriptures, such as the Bhagavad Gita, Upanishads, and the Buddha’s story. These texts deeply impacted and inspired them. Thoreau became somewhat of a renunciate at Walden pound, where he lived a rural life and wrote about his account. He referred to himself as a “yogi” in a letter to a friend. Most Americans never met a yogi in person before. Instead, their encounters were through this literature.

Encountering A Yogi

At the end of the 19th century, Swami Vivekananda, a Hindu monk, was sent to America to represent Hinduism at the 1893 World Parliament of Religions in Chicago. The event’s purpose was to bring representatives of different world religions and place them on a single stage. Hindus, Buddhists, Jains, Jews, Protestants, Catholics, Unitarians, and adherents of the Shinto and Zoroastrian traditions met together for the first time in modern history.

Swami Vivekananda went on stage and gave a speech that emphasized that no single faith is above any other religion. Vivekananda went on to introduce some of the ideas of yoga. In particular, a meditational yoga to the audience for the first time. Given his success, he stayed in the US for years. He founded Vedanta centers across America, which taught a form of meditation and concentration practices.

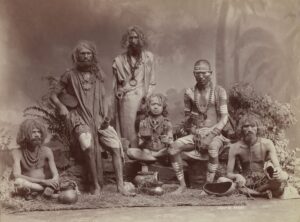

Yogis Gone Bad

During the late-medieval to the early-modern period (1700-the 1800s), groups of yogis became soldiers. They were armed with weapons and had financial and political power. The militarized yogis began to assert their dominance and fought one another for important trade centers around India. Yogis also fought against the British in the 18th century. British colonial powers deemed these aggressive yogis as a threat. When British rule in India officially arrived, many cultural practices were outlawed and vilified. Swami Vivekananda himself associated Hatha yoga with low-caste nuisances. Indian societies shunned Hatha yoga because this group of power-hungry individuals wrongfully misused yoga’s powerful practices.

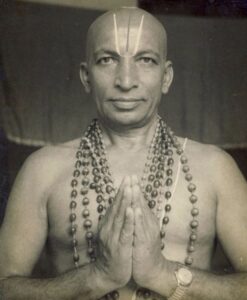

Yogis Gone Right: Tirumalai Krishnamacharya (1888-1989)

The way modern yoga is practiced and understood today is mainly from the system of Krishnamacharya. Let us just call him “Krish.” Krish is known as the “father” of postural yoga. He went through traditional education and studied yogic philosophy and Sanskrit from a very young age. When completing his studies in Varanasi, Krish wanted to find more in-depth yoga instruction. So he looked for a guru. Krish heard about Ramamohana Brahmachari, who lived in a cave in Tibet. Krish found Brahmachari and studied with him for some time in Tibet. Eventually, Brahmachari instructed Krish to return to civilization, get married, and then share his knowledge of yoga with others.

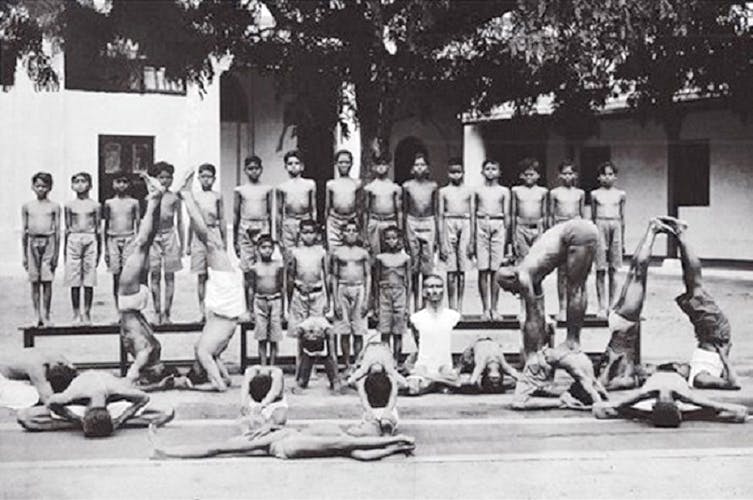

Krish returned from the mountains and established himself in Mysore. He was invited by the King of the Mysore in the 1930s to teach yoga to young boys at Mysore Palace. Physical yoga at this time was still very unpopular. British occupation also continued to be prevalent in India, and civilians faced oppression from the British in many ways. The King wanted to encourage these young men to develop healthy bodies and strong minds in the face of British Colonialism. He also wished to restore and reinvigorate Indian traditions. The King saw potential in Krish’s yoga and believed that yoga could be a mechanism to empower young Indian boys and men within their heritage. The King commissioned Krish to help reinvigorate the physical yoga tradition.

During this time, a larger global movement of various physical exercise systems was also developing. These practices included bodybuilding, wrestling, and Swedish gymnastics. There are strong parallels between these methods and the system of postural yoga developed by Krishnamacharya. All of these systems were practiced at Mysore Palace and likely came into contact and influenced one another. There seemed to be an exchange of methods and practices during this time. There’s no proof that modern asanas came from Swedish gymnastics or vice versa. Instead, the experimentation of the body was part of these larger global movements.

Paving The Path For Yoga In The West

Yoga in America in the 1950s-1960s still was considered strange even though it was becoming more popular. It took time before yoga could shed some of its stereotypes. One event in history that aided in the popularization of yoga in the West was the immigration policy act in 1965. The prior act regulated how many people from Asia could enter the US in a given year. The new policy lifted the immigration band and allowed an influx of Asian immigration to occur. During the mid-1960s, a wave of gurus entered the US and brought their teachings of yoga and meditation with them. Americans who craved something outside of their own established traditions were drawn to these teachings. The establishment of several ashrams around America occurred during this time.

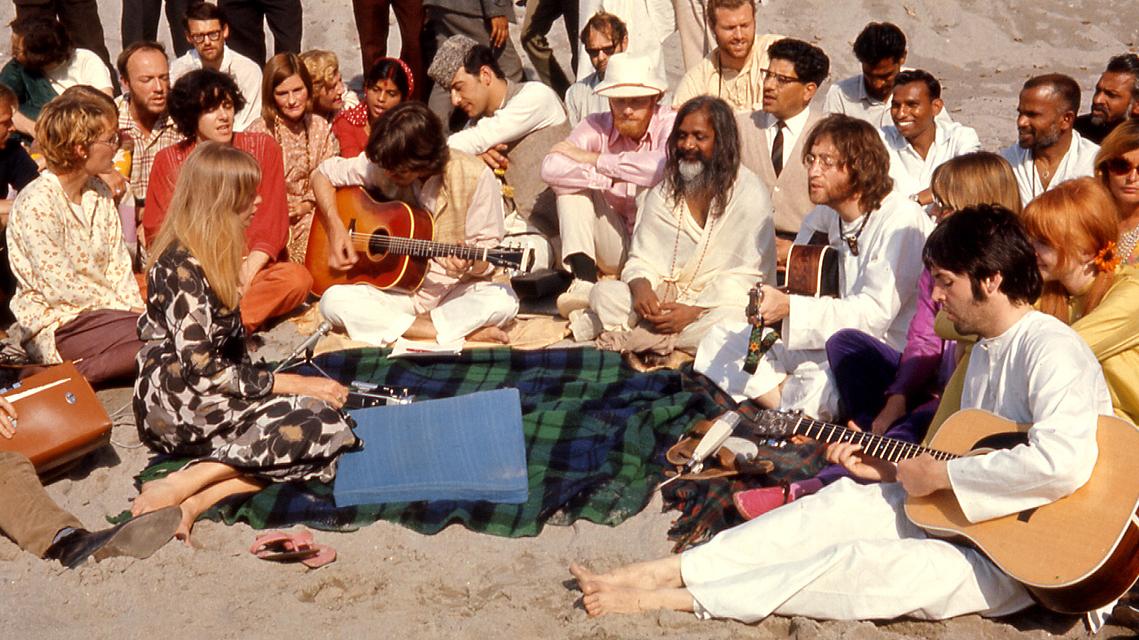

A second event that aided in yoga’s popularization was The Beatles’ visit to India. They traveled to Rishikesh, India, in 1968 and became interested in the yoga tradition. This lead to an increasing amount of interest in yoga in Western society. Yoga went from a counter-cultural practice to a popular trend.

Disciples of Krishnamacharya

The disciples of Krish and other influential Indian thinkers brought postural yoga to the West. Indra Devi was a Russian actress traveling the world. She became the first Western student of Krish in the 1930s. She has been termed “The Mother of Western Yoga.” She later moved to Hollywood, California, and opened a yoga studio. Many famous people went to her yoga classes, including Maralyn Monroe, although Yoga in the West was still not yet popular.

After the Immigration Act of 1965 passed, BSK Iyengar, Krish’s brother-in-law, and student, also visited the West. His style of yoga was termed Iyengar Yoga and focused on alignment and the use of props. Pattabhi Jois, another disciple of Krish, also made his way to America and brought with him the practice of Ashtanga Yoga in 1975. Only ten to fifteen students participated in Jois’ first workshop. This is a vast difference from the number of people who practice his style of yoga today.

Yoga & The Fitness Craze of the 80s and 90s

Yoga began to take off during the fitness craze during the late 80s into the 90s. The yoga industry began to develop with the launch of Yoga Journal magazine, Jane Fonda’s yoga workout DVD, and the fitness craze centered around Power Yoga. In the 2000s, yoga gained even more popularity when celebrities began to practice and promote yoga. This included Jennifer Aniston, Madona, and Sting were now practicing yoga. Yoga Journal Conferences became popular along with festivals with “famous” Western yoga teachers.

Moving Into The 2000’s

According to a 2016 Yoga Journal research study…

- There are 36.7 million US yoga practitioners, up from 20.4 million in 2012

- 34 percent of Americans say they are somewhat or very likely to practice yoga in the next 12 months – equal to more than 80 million Americans

- Students spend $16 billion/year on classes, gear, and equipment, up from $10 billion in 2012

- Women represent 72 percent of practitioners; men, 28 percent

- 74 percent of American practitioners have been doing yoga for five or fewer years

- The top five reasons for starting yoga are: flexibility (61 percent), stress relief (56 percent), general fitness (49 percent), improve overall health (49 percent), and physical fitness (44 percent)

- 86 percent of practitioners self-report having a strong sense of mental clarity, 73 percent report being physically strong, and 79 percent give back to their communities – all significantly higher rates than among non-practitioners

- All audiences surveyed agree that warm and friendly demeanor, clarity, and knowledge of yoga poses are characteristics that make for a great yoga teacher

- There are two people interested in becoming a yoga teacher for every one current teacher

- Half of yoga teachers have been teaching for more than six years

Present Day

I began to practice and learn about yoga over a decade ago. My own practice and knowledge of yoga has evolved and changed significantly since then. I started doing yoga to impress a boy. Then it turned into something I further explored to push myself physically. Eventually I became more aware of the placement and needs of my body. Slowly, my interests shifted to the effects of breathing techniques and sitting silently to help me gain some control over my restless mind. Now, while I continue to practice the physical components of yoga daily, I have become more focused on applying yogic philosophy into everyday aspects of my life.

I began to practice and learn about yoga over a decade ago. My own practice and knowledge of yoga has evolved and changed significantly since then. I started doing yoga to impress a boy. Then it turned into something I further explored to push myself physically. Eventually I became more aware of the placement and needs of my body. Slowly, my interests shifted to the effects of breathing techniques and sitting silently to help me gain some control over my restless mind. Now, while I continue to practice the physical components of yoga daily, I have become more focused on applying yogic philosophy into everyday aspects of my life.

Knowing The Past Helps to Determine Our Future

Yoga has changed continuously over time. The practice has innovated and adjusted to the needs and value system of the place it inhabits. As is the case with any discipline, it shifts and adapts according to that time and place when it travels to new cultures, geographies, and spaces. It is important to remember that the yoga we are practicing today relates to these earlier yoga practices but has gone through some pretty significant changes.

Learning about the different paths, practices, and philosophies that are a part of yoga’s history broadens the course an individual can take when on their yoga journey. There is plenty of wisdom to choose from that dates some 2,000-5,000 years back (depending who you ask). You only have a lifetime to learn and practice all of the tools this tradition offers. I challenge you to begin learning what works best for you in modern times to help you live an abundantly joyful life.

Kristin, Thanks for your lovely Blog where I am learning more about you and yoga. Great job!

Thank you, Liz! I really appreciate you taking the time to read my posts!